Like centuries of past greats, today's artists must find their voice to elevate the beauty of faith, famed professor Elizabeth Lev says

ANN ARBOR — Following her presentation at Angel Hall on the campus of the University of Michigan, famed art historian professor Elizabeth Lev left the audience with one ponderous question: What do Christians want to communicate through art today?

Lev’s lecture, hosted by the Kateri Institute for Catholic Studies at U of M, was the first in a yearlong series called “Life of the Mind,” a combination of public lectures and sit-down seminars, which this year will focus on the themes of art and science.

In her Sept. 21 lecture, "Communication Revolution: Christians and Art,” Lev, who is a professor of art history at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, a didactic consultant for the Vatican Museums and whose TED Talk on “The Unheard Story of the Sistine Chapel” has garnered nearly 2 million views, spent a little more than an hour giving a compact history of how Christians have communicated the Gospel message through artwork in different eras and artistic movements.

“What I'm really interested in is the question of communication," Lev said of Christian artwork. "Christians are out there to go forth and make believers of all nations; they are out to tell this good news. They've got a story to tell, a message they've gotten to transmit. How do they do that in the particular circumstances in which Christianity arises?”

Early Christians utilized artwork to communicate with the Romans, who were a “highly visual people,” Lev explained, using familiar images to convey the message of salvation — for example, the image of Christ as the Good Shepherd, which was derived from the Roman image of philanthropy.

“(Rome) is a very, very visual culture, and so the Christians respond in kind, and they create a visual lexicon so that they can communicate their story and they can talk to these people in a language they will understand,” Lev said. “Christians use pictures that the Romans will understand and will use them for complex theological ideas as they move forward.“

As time progressed, Lev said, the use of art changed for Christians — they switched from a storytelling mode to “art meant to transport you to another place in time” and later in the 12th and 13th centuries to convey the human nature of Christ.

“The art from the fall of the Roman Empire to around 1200 emphasizes Christ's divinity: He’s died on a cross, but he was resurrected,” Lev said. “There was a real emphasis on this divine nature.”

The implications of beginning to consider Christ’s human nature through artwork are significant, Lev said.

“If God takes on our form, our lives, our suffering, both physical and spiritual, and what it feels like to be abandoned, what it feels like to be hungry and thirsty, then it raises our experience in dignity, and it becomes possible to depict it in art,” Lev explained. “And so the artists start thinking more and more about how they are to represent the human experience.”

One way this message was conveyed was a new depiction of Christ on the Cross: instead of the stiff, straight-staring Christ on the cross popularly depicted up until that point, artists began to paint the lifeless body of Christ–head down, arms spread in pain, and heavy abdomen.

“It was very, very, very disturbing in its day, as a means to get people's attention and start thinking when we talk about Jesus's death and resurrection," Lev said. "Jesus died before he was resurrected. This intense thinking about his human experience is very important.”

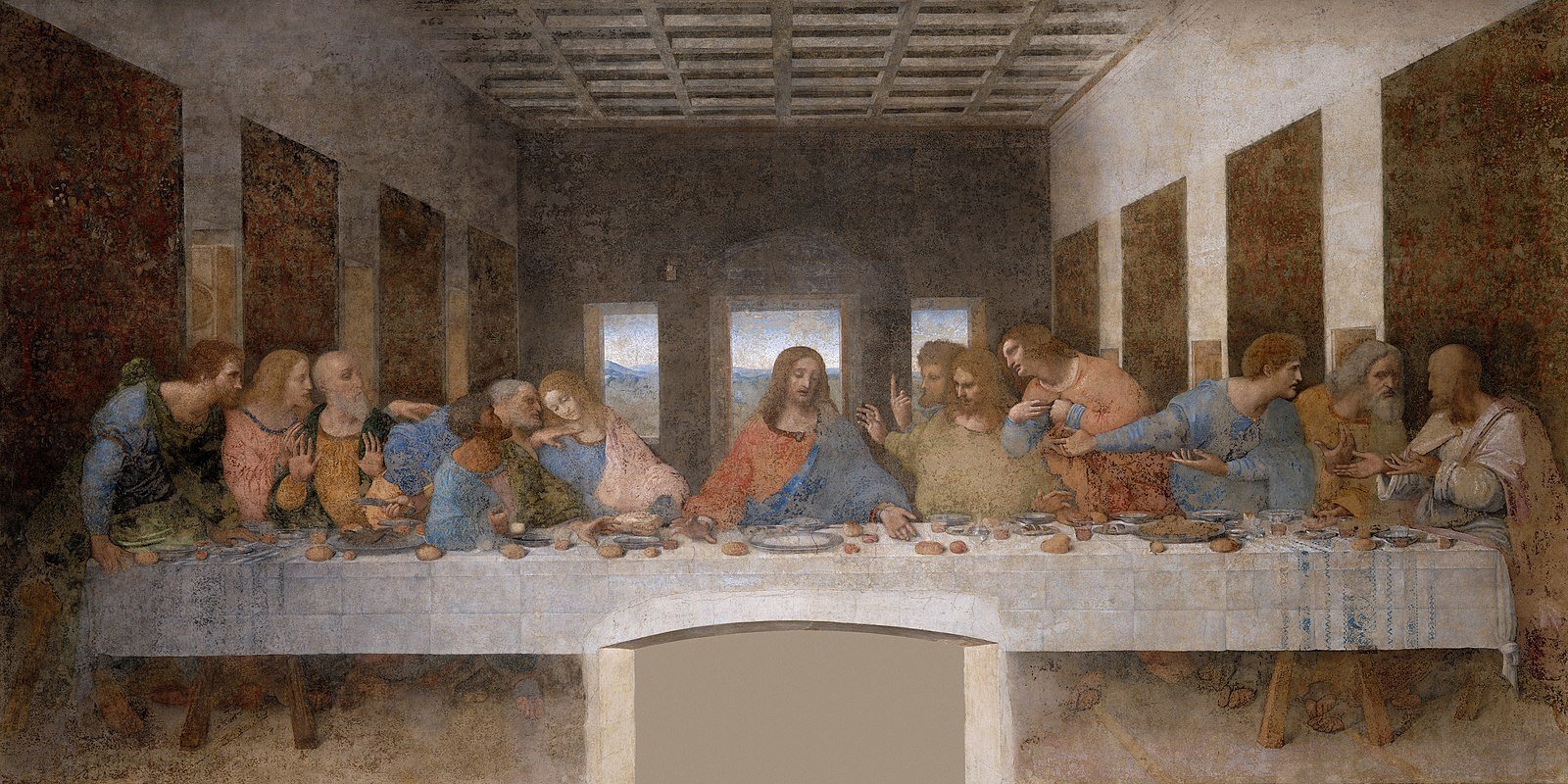

As the Renaissance was introduced, math and science advanced, and artists began to produce one-point linear perspective works of art — mostly famously Leonardo da Vinci’s "The Last Supper."

"In Leonardo Da Vinci's 'The Last Supper,' the beautiful use of the one-point linear perspective will draw your eye to the head of Christ, but in this beautiful way so that there's a flow from the head of Christ outwards, sort of rippling in the grouping of the apostles,” Lev said.

Da Vinci wanted to draw the viewer into the scene not just to be a part of the Last Supper, but to experience the psychological and spiritual impact of the isolated Christ, Lev said.

“The point of the composition here is to invite us to think for a moment, to attempt in our own little weak way: ‘What is it like to be that man, who is saying, 'One of you will betray me?’” Lev emphasized.

As the Church continued to consider what message art should convey, Christians called upon artists who were attuned and ready to convey the message of the Gospel through art, sometimes in new ways that would once have been rejected. Lev pointed to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, simply known as Caravaggio, who in 1599 painted the “Calling of St. Matthew” next to the altar of the Contarelli Chapel in Rome.

Lev explained that the timing of this commission was significant, as 1600 was a jubilee year, and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims were expected to descend on Rome in search of indulgences, forgiveness, and a way to change their lives and deepen their faith. Caravaggio’s “Calling of St. Matthew” was a retelling of an age-old story, but the young artist found a way to tell it that communicated with this new expected audience.

The painting displays a decadently dressed St. Matthew surrounded by his posse seated at a table, and is confronted by two men, the younger of whom points into the middle of Matthew's group as if to say, “Follow me.”

“But of all the men in that group, Matthew presents in a very unique fashion. He looks up and points to himself and responds in the way that every epic hero ever has responded, from Achilles all the way down to Luke Skywalker: ‘Who, me?’” Lev said.

Lev pointed out how Matthew’s other hand remains on the coins on the table, while his feet are slightly raised as if he is ready to get up and follow.

“But the problem is that (he) doesn’t have a lot of time to make that decision because (of Christ’s feet): one raised foot and one foot that is down; Jesus is leaving,” Lev said. "What is Caravaggio saying? Catch the moment now — of all those people sitting at that table, Matthew is the one who looked up at just the right moment and received the call and went.”

Lev ended her presentation with the implication that the Church has not had a remarkable Renaissance in some centuries, but she believes it can happen again.

“The problem we find today is this: What is it that we want to communicate?” Lev asked. “All of these other periods we have been looking at had an idea of what they wanted to say. Christian art knew what it wanted to say and found artists who found a way to say it. This is where we are: the big question at the end of the day as we face going into the third millennium is, ‘What do we do with art now?’ What is the message that we want to tell people that is the most compelling about our faith, and how do we get the artists to represent it?”

For Lev, the solution can’t exist without beauty at its core.

“St. Augustine had it right when he talked about beauty ever ancient, ever new, and he taught us about how beauty can call and shout and awaken us from our blindness and our depths,” Lev said. “Perhaps we can somehow recover that in our age.

“The thing I don’t believe will help is to present ugly,” Lev added. “I don’t believe that attracts people. It doesn’t help anyone to get to that altar and think, ‘Life stinks,’ and think about how brutal and awful the world is when you walk through that door. I am usually walking through that door to get away from all that.”

Artwork should make clear that Christians gave their best, their time and sacrificed for the glory of God, as a way to show that they take Him seriously, Lev said.

To do so, artists don’t need to replicate Da Vinci or Raphael, Lev said — they can have their own vision.

“Artists should be invited to understand, ‘What are you depicting? What are you doing?’” Lev said. “You are helping, you are accompanying, you are encouraging people to go from that space on the outside where we are surrounded by brutality and injustice and all those things to the place where we find comfort, hope, truth and light, and that makes us feel uplifted like we are going someplace.”