Sean M. Wright interviews Turner Classic Movies' "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller about his new book, Dark City, and how the genre of film noir may — or may not — intersect with Catholic thought.

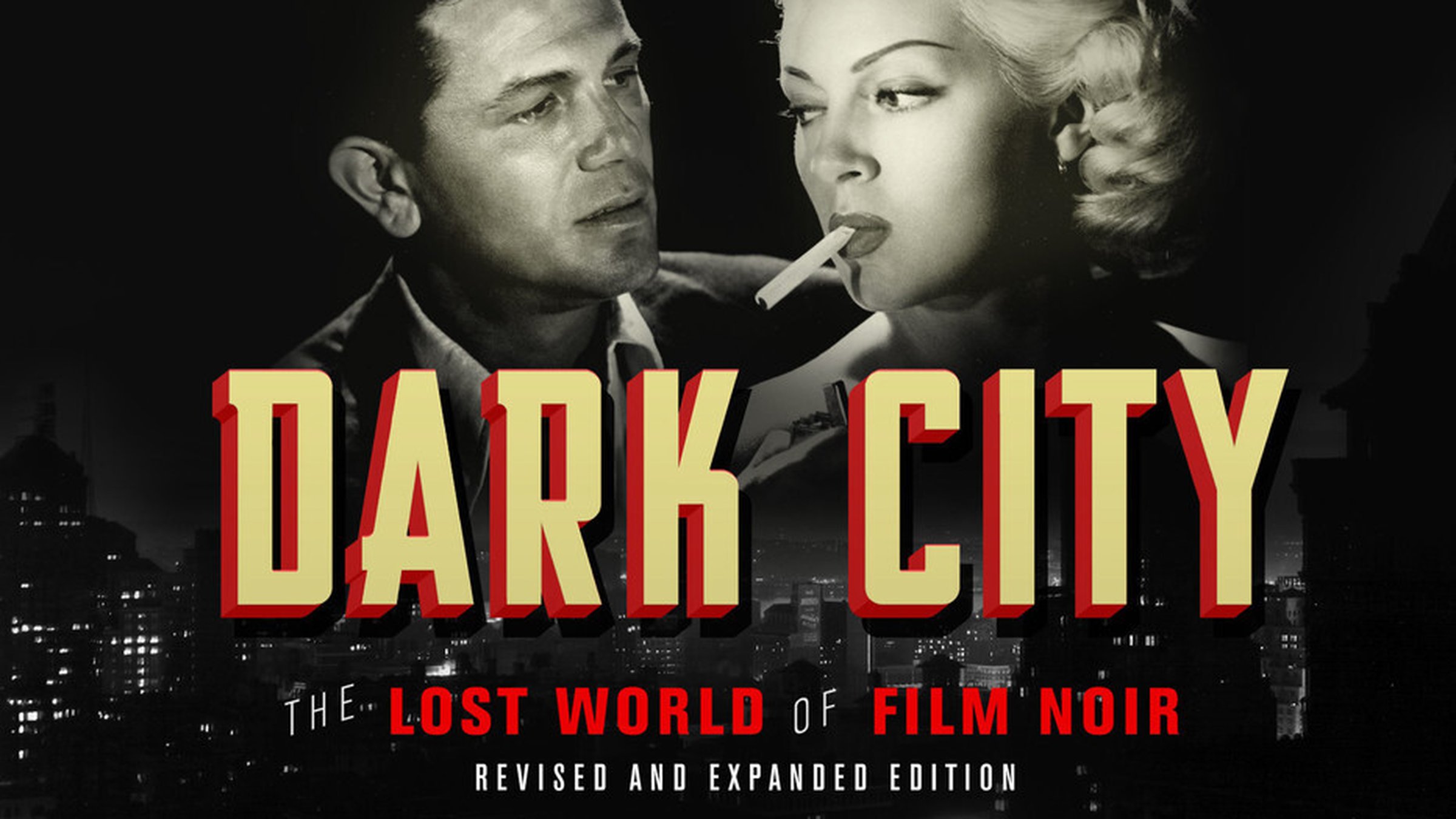

Dark City (Running Press, 2021) is an extensive, enjoyable excursion through the more sordid areas of B movies known as film noir. It was written by Eddie Muller host of Turner Classic Movies’ “Noir Alley” is the nation’s most visible expert on the subject.

Dark City, a superb book devoted to many aspects of film noir, is presently being sold at all the usual bookshops, brick and mortar, as well as online. The book’s author, Eddie Muller, founder and president of the Film Noir Foundation, A recognized film critic, reviewer, author and host of Turner Classic Movies’ “Noir Alley.”

Eddie and his staff are remorselessly comprehensive in their research. Each film is bookended with Eddie demonstrating an encyclopedic expertise in the making and preservation of each example of noir, relating fascinating details about a film’s history, cast, producers, writers, directors, cinematographers and the rest of a film’s crew.

As founder and president of the Film Noir Foundation and co-programmer of the San Francisco Noir City film festival, Muller has been instrumental in saving these movies from neglect and destruction and has sparked greater public awareness of the noir art form. We pick up the conversation begun in the previous installment of Detroit Catholic:

# # #

SMW: What biblical themes are in film noir? For instance, I see Edmund O’Brien’s character in DOA as inspired by Job, but a Job without God, who seeks his murderer without expecting any salvation in an afterlife.

EM: Tough one; I haven’t studied the Bible in a few years. The relationship between Joe Morse [John Garfield] and his brother Leo [Thomas Gomez] in Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil certainly has a Cain and Abel aspect to it, in that Joe’s surrender to the dark side (he’s a fixer for racketeers) leads directly to his brother’s death, and an inspired ending suggesting a quest for spiritual redemption.

SMW: So, there is a kind of biblical tension between good and evil in noir?

EM: Noir stories are almost always tales of temptation, with spectacular falls from grace — so it’s pretty easy to relate them all to the tale of Adam and Eve. Noir fans are just as likely to argue the relative guilt of the men and women in these films as Bible scholars are to argue about whether it’s Adam or Eve who’s really responsible for getting them tossed out of Eden.

SMW: Ah! Mitchell Leisen's tale, Bedevilled (1955), presents temptress Anne Baxter almost causing Steve Forrest, studying for the priesthood, to leave the seminary for her "forbidden fruit." Do you see any echoes of the serpent's offer in Genesis?

EM: I confess: I haven’t seen it yet. Although I have no doubt Anne Baxter could tempt a man to leave the seminary. I have heard stories … But now you know! See? More second thoughts about what I left out!

SMW: Would you consider Barton Keyes [Edward G. Robinson], the gruff, truth-seeking claims manager in Double Indemnity, and frequently beat-up detective Philip Marlowe [Dick Powell] in Murder My Sweet, as Christ figures? Are there any other characters fitting the role?

EM: I’m leery of answering. I’ve found that “Christ symbolism” is one of the most abused notions in film criticism.

SMW: If the idea is that common there must be something to it.

EM: Well, it seems anytime characters stretch out their arms they are assuming a “Christ-like pose” which leads to all sorts of wild interpretations of the character and the film. I’ve heard some theories about Marlowe as a Christ figure, which I don’t really see, but I can honestly say this is the first I’ve heard it applied to Barton Keyes. Interesting. I’m going to think about that.

SMW: Would you describe the roles of women in most examples of film noir as femme fatales, plucky wives / girlfriends, heartless barflies, or reformed criminals?

EM: OK, you hit my hot button. If I have one goal left to achieve in my role as “Czar of Noir,” it’s to correct this notion that women in noir are one-dimensional cartoons — either the evil femme fatale or the saintly (and boring) “good girl.”

SMW: Hold on! I’m asking your opinion about the roles women take in noir.

EM: All right. But the most subversive thing in the noir movement may have been its depiction of women, specifically competent, professional, self-reliant working women, as not only the salvation of men, but of society as a whole. It’s astounding to see how many of these women are in noir films.

SMW: Women of character, in other words.

EM: Yes, very much. They’ve just been overshadowed by their no-good sisters who don’t want to work for a living, who’d rather manipulate men into doing the heavy lifting for them.

SMW: Who would you say exemplifies this role best?

EM: Watch any movie of the noir era starring Ella Raines — Phantom Lady, Uncle Harry, The Suspect, The Web, Impact — she is the embodiment of the smart, resourceful, self-possessed modern woman. Watch any movie produced by Joan Harrison, Alfred Hitchcock’s protégé, especially They Won’t Believe Me, and you’ll see well-written roles for women — real women, not caricatures.

SMW: A priest being involved in crime of any sort would be big news in the noir era. I Confess (1953) is a favorite of several priests I know. In Dark City you describe it in terms of being a Hitchcock oddity but don’t you think it has influenced later films?

EM: I give I Confess more attention than many writers focusing specifically on Hitchcock. My angle on the director was that he tended to belittle his own work when it revealed too much of his personal quandaries where faith was concerned. He’d retreat into the guise of a prankster, which worked well for him professionally. But you see a different Hitchcock in I Confess and The Wrong Man (1956), which, not coincidentally, are the among the most “noir” of his films.

SMW: In as beautifully realized a book as Dark City, it seems that you might have included a chapter called "The Church Around the Corner." Religion, specifically Christianity, meant a great deal to people in the US during the noir era. Think you might add such a chapter to the Dark City in a possible future revision?

EM: It’s an intriguing thought, though to be honest it would be such a lightning rod that people might only focus on that chapter. Sadly, “with us / against us” reactions seem to dominate any discourse on religion these days.

Instead, I wove my thoughts on the subject into the Blind Alley chapter, considering the notions of fate/faith/belief as they applied mainly to the works of Cornell Woolrich and Hitchcock. It’s in there, I just didn’t opt to make it a stand-alone chapter; I don’t think there were enough noir films specifically rooted in religion to fill out a chapter.

Still, there are thematic threads in that regard that run throughout the book. Honestly, the Church was a predominant factor in the film noir movement because so many artists were struggling against the constraint of the Production Code, which was largely an extension of the Catholic Legion of Decency.

SMW: Don’t forget there were many local censorship boards. We don’t hear that something was “Banned in Boston” any more.

But what do you think of including Hitchcock's The Wrong Man and Detective Story (1951) in such a chapter on religious themes? The main characters are greatly influenced by their Catholic backgrounds: Henry Fonda seeks comfort by reciting the Rosary; William Bendix intones the Act of Contrition over the dying Kirk Douglas, devastated by news of his wife's admitting to having an abortion and his struggle to forgive her.

EM: As I noted, The Wrong Man is an essential Hitchcock film, and I do discuss it in some detail how it fits, uneasily, into the director’s oeuvre. I think it’s much more of a film noir than most critics give it credit for. For me, these films fit snugly into my thematic chapters Blind Alley and The Precinct.

SMW: You describe Kirk Douglas' character in Detective Story as committing suicide by subduing Joseph Wiseman’s crazed psycho character before he killed innocent bystanders. Might this be better considered a selfless act, an example of what Jesus described as "Greater love than this no man has, that he lay down his life for a friend" (John 15:13)?

EM: I’m sure some people perceive it that way, and I’m certain that’s how it will be described at Jim McLeod’s funeral service. For me, the theme of Detective Story is the danger of the “serve and protect” mentality veering into self-righteous fury.

McLeod had so little forgiveness in his heart. I tend to see this last heroic act as something instinctive and reactionary, more than an act of selflessness. As a behind-the-scenes aside, it should be noted that dying at the end was essential for Kirk Douglas — he goes out the same way in Champion and Ace in the Hole, as well — all made right around the same time.

# # #

Eddie is at his catechetical best in this segment. He admits to the use of biblical themes and their importance in many noir films. With some justification he bridles against reviewers claiming to see detectives as Christ figures simply because they try to solve crimes and set right what went wrong.

Eddie paused when considering the claims manager played by Edward G. Robinson in Double Indemnity. He is an incorruptible man seeking out attempts to cheat his company but also shows a richness of mercy. His final scene with Fred MacMurray is particularly affecting.

Yet again, Eddie rails against the Legion of Decency. This organization, never officially part of the Church, was founded in 1934 when the vast majority of U.S. Catholics tenaciously clung to their faith and morality in the midst of a unsympathetic, sometimes hostile culture.

Much of this formation has been dissipated by the media’s fixation on sex and monetary scandals within the Church, while modernist/progressive/secularist teachers and instructors found in every level of Catholic education go out of their way to undermine confidence in the truth of Catholic belief and the authority of Holy Scripture.

However, these problems are not part of Dark City, which is devoted to a particular type of storytelling with film. This is one of those rare coffee table books which is not only beautifully laid out but informative to the nth degree, a pot of cinematic stew filled to the brim with tasty tidbits. Any film buff worth his DVR will find Eddie Muller’s Dark City required reading and a most agreeable addition to his library of movie lore.

Eddie will be discussing aspects of film noir at the Annual TCM Film Festival taking place in Hollywood, April 21-24, 2022.

[Part 3 of Eddie Muller’s interview will appear in the next installment of Detroit Catholic.]

Sean M. Wright, MA, an Emmy-nominated TV writer, is a Master Catechist for the archdiocese of Los Angeles and a member of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, CA. He responds to comments sent him at [email protected]