An ancient story Ile tell you anon

Of a notable prince, that was called King John;

And he ruled England with maine and with might,

For he did great wrong, and maintein'd little right.

— Anonymous English Folk Song, date unknown.

We left John Lackland, king of England, ending a seven-year-long argument with Pope Innocent III — an argument of his own creation. But, then, he came from a contentious family.

In the 1100s, the family ruling Anjou, a county in France, took its surname from Genista, commonly called the “Broom plant,” a shrub having small, stiff, brush-like foliage. Geoffrey V, count of Anjou, and duke of Normandy, habitually adorned his cap with a sprig of the fragrant, yellow flowers of the planta genista. His family thus became surnamed “Plantagenet.”

Geoffrey Plantagenet married Matilda, daughter of Henry I, king of England. Their son, Henry, eventually married the wealthiest and most powerful women in western Europe, the vastly intelligent, highly regarded Eleanor, duchess of a huge expanse of land called Aquitania, the southwestern half of France.

Henry I died in 1135. Geoffrey Plantagenet’s son, Henry — count of Anjou, Touraine and Maine, duke of both Normandy and of the Aquitaine — inherited the island kingdom of England, along with parts of Wales and Scotland. As Henry II, one of England’s more notable kings, he introduced more than 300 years of Angevin rule to England. Even so, toward the end of his life, he had to put down the rebellion of three of his five sons, who were abetted by their mother, Eleanor.

Richard succeeded his father. Despite the Lionheart’s spending no more than 10 months of his 10-year reign in England, Richard’s reputation as a warrior was such that he was extolled as the prime example of the “gentyl and parfit knyght” within the newly minted code of chivalry, largely developed at the court of the previously exiled Eleanor, his still-prominent mother. Aided by lays and ballads, the airs sung by minstrels and troubadours, the chivalrous ideal of Christian knighthood developed and spread across Europe. Within England the ideal became the use of Might in the service of Right, to act justly and protect God’s Church and all women and orphans, rich or poor, Norman or Saxon.

The Catholic Church gladly promoted chivalry to help tame and civilize the brutal cultures she encountered. The Church believed it necessary to refine the barbarism of European tribes with music, art and literature by instilling within them a sense of Romanitas, a system developed during the apex of the Roman Republic. Romanitas extolled the civic virtues of duty, patriotism, courage, restraint and personal dignity as signs of good citizenship. Along with these, the Church added a greater respect for women, based on her reverence for the Blessed Virgin Mary as “help of Christians,” interceding to God for her children’s every care and interest.

The Church realized that civic virtues made it easier to preach the Gospel’s spiritual values. All of which led to a deep reverence for God, His commandments and the sacraments.

Richard’s favored status continued across generations. With his character highly burnished in Victorian novels, most notably in those by Sir Walter Scott and Howard Pyle, aided by many motion pictures, generally centering on the character of Robin Hood, the Lionheart continues to be presented as the monarch par excellence.

And then there was John.

As prince, among other depredations, he collected the skulls of his beheaded adversaries in Ireland. He attempted to turn his father, Henry II, against Richard to keep him from becoming king. Plotting with Philip Augustus, king of France, John attempted to seize England’s crown while his brother, the Lionheart, seized and held for ransom on his return from the Third Crusade, was left languishing in an Austrian castle.

The chronicler, Richard of Devizes, remembered John as a young prince screaming in frustrated fury at the king’s chancellor, Longchamp: “His whole person became so changed as to be hardly recognizable. Rage contorted his brow, his burning eyes glittered, bluish spots discolored the pink of his cheeks, and I know not what would have become of the chancellor if in that moment of frenzy he had fallen like an apple into his hands as they sawed air.”

As king, John’s reputation grew no better. He allegedly murdered Arthur, the duke of Burgundy, his 16-year-old nephew, a rival claimant to the throne. He levied unfair taxes and land seizures on barons, the clergy and minor landholders alike. He forced his knights and barons to fight in foreign wars to protect the Angevin empire in France. The nobles could escape pledging their men at arms and themselves to John’s endless defensive wars, but only by paying excessive scutage charges so John could hire mercenaries to fight instead.

Largely irreligious, John rarely partook of Holy Communion. Although he held his own in theological discussions, he seemed to care not a whit about where his immortal soul ended up. Disputing with the pope over the see of Canterbury, John passed a sentence of outlawry on the clergy (later revoked). Says Robert Folkestone Williams in Lives of the English Cardinals (1868): “John burst out into uncontrollable fury against Pope and cardinals, swearing ‘by the teeth of God’ to drive every priest out of the country, and slit the noses of every Roman he could find in it.”

The king allowed England to remain under interdict for six years, while he was excommunicate for four years. On top of all that, in secret correspondence with Mohammed al-Nazir, sultan of Morocco, John promised that he and England would embrace Islam in exchange for the Saracen’s support against his enemies. The sultan did not take him seriously.

In “The Rule of History” (The New Yorker, April 12, 2015), Jean Lepore adds: “He also had a passel of illegitimate children, and allegedly tried to rape the daughter of one of his barons (the first was common, the second not) … When his noblemen fell into his debt, he took their sons hostage. He had a noblewoman and her son starved to death in a dungeon. It is said that he had one of his clerks crushed to death, on suspicion of disloyalty.”

Is it any wonder the medieval chronicler Matthew Paris concluded his summation of John’s character by writing, “Foul as it is, Hell is made fouler by the presence of John”?

In 1213, now acknowledged by King John, Cardinal Stephen Langton returned to England as archbishop of Canterbury and primate of England. The former rector of the University of Paris, he had come far. And, now, this son of an ordinary Lincolnshire landowner lifted the pope’s ban and welcomed his king’s return to the bosom of Holy Mother Church.

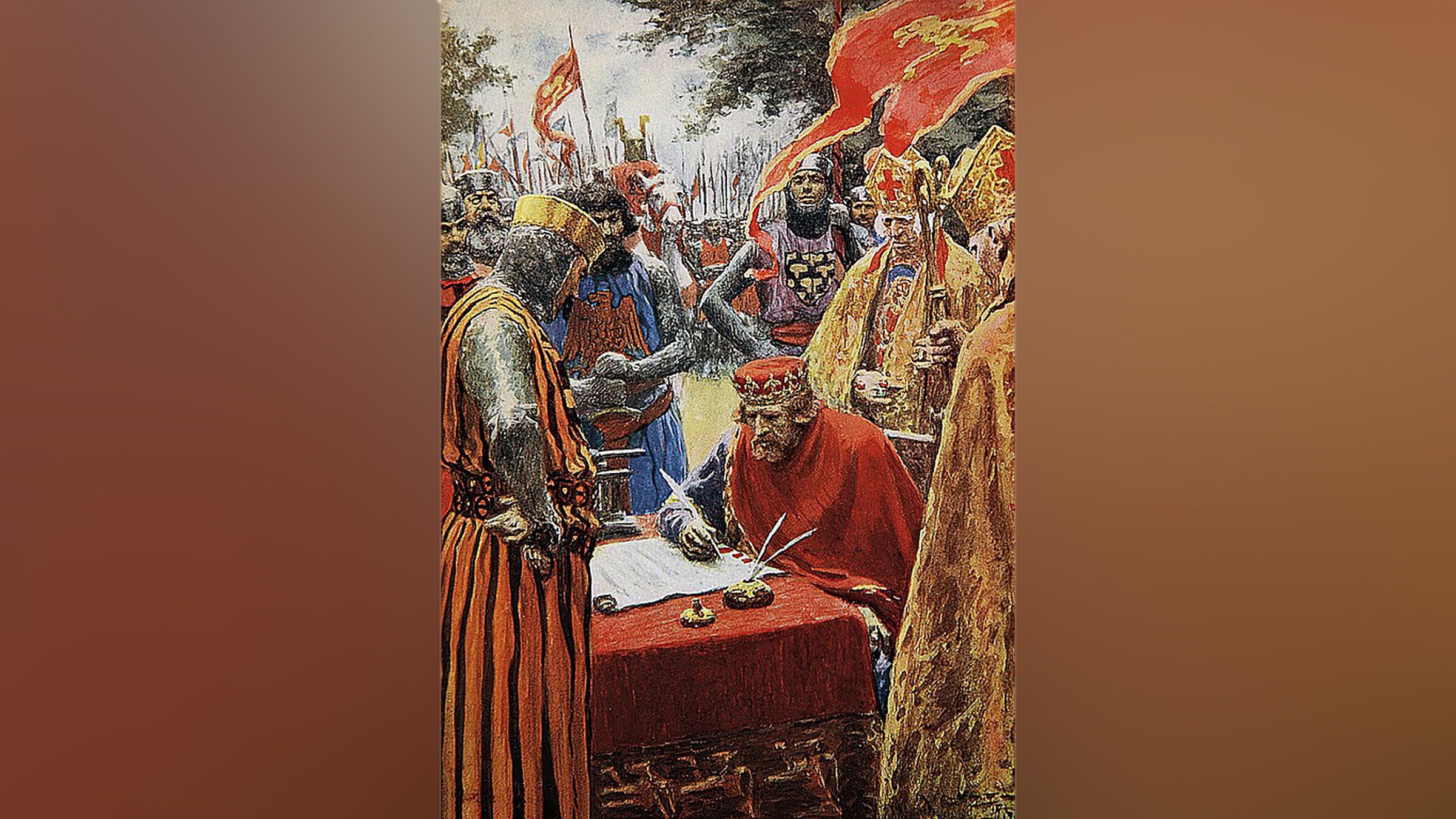

Into John’s coronation oath in 1213, Archbishop Langton inserted the Charter of Liberties proclaimed by John’s grandfather, Henry I, as part of his coronation oath in 1100. The Charter of Liberties was unique among the feudal nations of Europe, as a voluntary limitation of royal power with the force of law.

The Charter was a response to abuses committed by William II (William Rufus). It specifically concerned abuses such as over-taxation of the barons or allowing bishops’ sees to fall vacant unless purchased through simoniac extortion. Also condemned was pluralism, the practice of allowing one bishop, a royal favorite, to hold many sees and derive income from all of them while knowing little about the state of the Church in any of them.

For the sake of peace, Henry I had upheld the Charter of Rights, solemnly agreeing to it as part of his coronation oath. He then promptly forgot about it. As did John.

Stephen Langton, the Cardinal-Archbishop of Canterbury, did not forget.

Sean M. Wright, an Emmy-nominated television writer, is a Master Catechist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. He is also part of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, CA. He responds to comments sent him at [email protected].